I earned 0 Euros from maintaining OSS software for years, and I thought that’s the way things are. I finally looked into ways to monetize my projects last year and in this talk I want to share what I learned so far. It didn’t make me rich (yet!), but I built my first sustainable side-project with analysis-tools.dev ✨.

I’ll talk about this and other projects and the mistakes I made on the road towards sustainability.

Related links and resources:

- Podcast by Caleb Porzio about why building a business around Github sponsors is so hard.

- The Changelog Podcast — It’s OK to make money from your open source with Zeno Rocha.

- Nadia Eghbal talking about Maintenance of our essential info-structure. She also wrote a book on that topic called Working in Public.

- Generating income from open source by Vadim Demedes, which explains different ways to monetize your projects based on various real-world examples.

Find a full transcript of the talk below. (Sorry for the wall of text.)

This is my talk about earning money with Open Source, which I gave at the Web Engineering Meetup Aachen at the end of 2020. The organizers gladly allowed me to share it on my YouTube channel. I’m basically trying to answer the question: “Why am I not making 100k on Github?”. I’m talking about finding corporate sponsors for myself and the long road towards sustainability of open-source maintenance.

You might not even want to start. This is a talk for those people that have the mindset that it’s probably not worth it to spend that much effort on Open Source if it takes so long until you find success. Now, this talk turned out to be a little grim. I had this very motivational talk in mind, but in reality, it’s hard, and by hard, I mean it’s really hard.

I just want to get this point across and maybe still motivate you to do it but first: why am I entitled to talk about this? I’ve been doing Open Source for 10 years over 10 years now. This is a talk dedicated to my former self maybe 15 years ago. I work at trivago, which is a hotel search company based in Düsseldorf. I have a blog at endler.dev. Like everyone and their mom, I also have a YouTube channel. It’s called Hello, Rust! and I’m extremely active with one video every two years. Hence, you definitely want to subscribe to not miss any updates. But today, I want to talk about Open Source, and I have a very sophisticated outline with two points my journey and revenue models.

Let’s go back all the way to 2010. The world definitely looked a bit different back then.

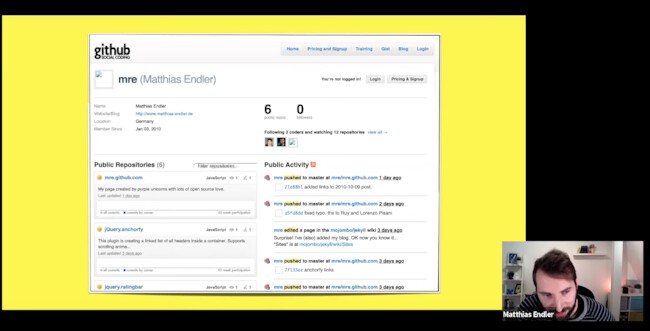

This was Github, and I was a bit late to the game. I joined in January 2010, and by then, Github was already two years old, so my username was taken. I usually go by the handle mre on platforms, and I noticed that this handle was not used by anyone, so I just sent a mail to support and asked if I could have it, and then I got an answer from this guy saying “go for it.” It was Chris Wanstrath, who goes by the handle defunct, and he’s the former CEO of Github, and at this point in time, I was hooked. I really liked the platform. I really liked how they worked very hands-on with Open Source. I used it for some projects of mine; you can see in the screenshot that I uploaded my blog, for example, because they host it for free. It was built with Jekyll, and you just push it to their site. Then they statically generate it, and it’s done. It goes without saying that nothing has changed in the last 10 years because my blog more or less still looks like that. It’s not built with jQuery and Jekyll anymore, but with zola and Cloudflare Worker Sites, but it’s more or less the same thing. For preparing for this talk, I wanted to take a step back and see where I was coming from and where I am right now, and probably the best way to do it is to look up some statistics and see if the number of repositories over time would give me some insights. So I queried the Github API for that.

You can see it’s pretty much a linear graph from 2010 all the way to 2020. Except for 2018, where I reached peak productivity, it seems, but oh well. In the end, it’s more or less a linear thing, and you might say you put some work in you get some feedback out, but in reality, it’s different. There is a compound effect. If we look at my number of stars over time, you can see that more or less it started very slowly, and now it’s sort of growing exponentially, so right now, we are at 25.000 stars across all projects. Another way to look at it would be the number of followers. That’s kind of a new metric to me, but I did look up some statistics from archive.org (because Github doesn’t have that information through their API), and again, it’s more or less exponential growth.

You put some work in, but you get a compound effect of your work plus some interest out. This is not luck; it’s work. It means you know what you’re doing. At the same time, there’s the elephant in the room, and that is it’s just a pat on the back. We have earned zero dollars until now, and one question you might have is how do you monetize this effort.

First off, is it an effort?

Well, I don’t know about you, but I probably spend two or three hours on average per day on Open Source: thinking about Open Source and creating new projects, but also maintaining and code review, so it really is work, and it’s a lot of work, and you more or less do that for free.

There’s nothing wrong with doing things for free and doing it as a hobby, but in this case, you are supposed to be working on whatever you like. Open Source is not like that; sometimes you have obligations, and you feel responsible for maybe helping people out, which is a big part of it. You do that next to your regular work, so it can really be a burden. If you don’t know by now, making this somehow valuable is hard, it’s really hard. I want to talk about some ways to build a proper revenue model from Open Source. It goes without saying that this should probably not be your first focus if you saw the graphs before, but once you reach a point where you want to get some revenue, you have a couple of options. I don’t want to talk about doing Open Source as part of your business, and I don’t want to talk about bigger companies and more significant support here. I want to focus on a couple things that everyone can do. Sponsoring [on Github] is one. Offer paid learning materials on top of your normal documentation. For example, you might have a video series that you ask for money. Sell merchandising like Mozilla does. Consulting next to your Open Source business Services and plugins like writing an ADFS plugin or high availability functionality are very common examples for paid features targeting enterprises.

But let’s start with the basics. Let’s start with point number one, sponsoring. There are two types of sponsoring: the first one is individual donations. Individual sponsoring is what Github Sponsors is all about. If you want to earn money [with that model], you have to think about the funnel, and you have to think about how you capture people’s attention and how you monetize that. It starts with a product, [which] can be anything. From there, you generate interest, and this interest creates an audience, and that audience eventually might pay for your service, and this is actually the entire secret. It’s how you earn money with any product, and with Open Source, if you want to attract sponsors, you build a product people want.

If you transfer that to Open Source, building a project is maybe a repository, and the stars indicate the interest of the audience. The audience itself is made out of followers (personal followers or followers of a company), and those followers might or might not become sponsors in the end. Now, I know stars are a terrible metric for popularity because some people use stars differently than others. For example, some use it as bookmarks to check out projects later, others want to thank the developers for maybe putting in a lot of effort, and so on, but it’s a good first estimation.

Now, think about the following. Think about the number of stars I have and the followers and the number of sponsors. Think about my “funnel” right now. I told you that I have 25.000 stars and roughly 1000 followers, and out of those, I have three sponsors, so the ratio between the stars and sponsors is 0.01. That looks pretty grim. It means you need around 8.000 stars to attract a single supporter. I was wondering: “maybe it’s just me?”. Maybe the top 1000 Github maintainers did not have that problem. Well, it turns out it’s exactly the same schema. If you take the top 1000 Github maintainers and look at their sponsors, it’s again a pretty grim picture. For example, looking at the median, you look at 3421 followers per person and a median of zero sponsors. That’s zero percent if my math is correct, and if you look at the average, you even have 5430 followers (because Linus Torvalds pushes that number up). You have 2.8 sponsors out of that on average, and that is 0.5%, which is a bit more than I have, but it’s roughly in the same ballpark. Now think about this: Github has 40 million users, so that means the top 1000 maintainers make up 0.0025% of the entire community. The median income of those maintainers on Github is basically zero.

That in and on itself is maybe not the biggest problem, but keep in mind that the Github revenue of 2019 was 300 million dollars. I read that comment on Hacker News yesterday:

I have sponsors on Github and rake in a cool two dollars per month. It’s obviously less after taxes, so I have to have a day job.

So this is clearly not working. You have to think of different ways to monetize Open Source, or you just wait until Github Sponsors becomes more popular – whatever happens first. One way I just want to quickly touch on is the notion of sponsorware. It’s kind of a new concept, and some people haven’t heard of it before. I honestly really like it. Generally speaking, you create a project, and you keep it private. You talk about it on Twitter, though or any other platform, and you say: “hey, I’m building this, but if you want early access, you have to become a sponsor,” and once you reach a certain threshold of sponsored sponsors, or income or whatever. Then you make a project public. This initial example that I showed you, where someone was earning 100k on Open Source, is from someone doing just that. He’s building products and services, talks about them, and then makes them open for everyone in the end.

This has some advantages: first of you get early feedback from people that really believe in your mission. Second, you don’t have to work for free all the time, and third, you might also create an audience and hype from your projects. The disadvantage is that if you are a hardcore Open Source or free software believer, this goes against your ethic. You want the software to be open, to begin with, without any additional requirements. So you really have to make up your own mind about that. I tried, and I have an early access program, which I only share with sponsors. [My first sponsorware was a] tool for getting Github statistics. [The statistics from this talk were] created with that tool. I think you need a big audience to pull that off. The question is if you want to put that much effort in, or you just want to make it open in the first place and think about other revenue models. However, I think still it’s a very interesting concept, and we might see that [more] in the future, so you know how it looks like now, and you have a name for it.

Another one is corporate sponsoring. This is a double-edged sword because corporate sponsoring means that a company gives you money and sometimes wants something. They might want additional support, or they want the bug to be fixed, and more or less it feels like you are somehow beginning to work for them, but nevertheless, those companies put in quite a big amount of money into Open Source these days. Looking at two big companies, Facebook and Google, they invested 177k and 845k respectively into Open Source over their lifetime on Open Collective, a platform for collecting those donations. That’s really great. We need more companies doing that, but also, as a little side note and maybe as a little rant, I believe that those companies are doing way too little.

Facebook’s revenue last year was 70 billion, and Google had 160 billion, which is nothing to be ashamed of, so I wonder really if this is the most they can do. Of course, Google, for example, also donated to other projects like Mozilla, and they also organize meetups and so on. But do you really think that Facebook and Google would exist today if there was no Python or web server or Linux back in the day when two Stanford students tried to build a search engine? Sometimes I feel that Fortune 500 companies really don’t understand how much they depend on Open Source and how many people depend on a few people who maintain critical parts of our infrastructure.

I don’t think they invest nearly enough into Open Source. What a lot of people think is that Open Source works like the panel on the left where you have a full room of engineers trying to figure out the best way to build a project, and in reality, it’s more or less someone working late at night to fix bugs and doing it because they believe in it. The public perception is probably wrong, and a really small group of people who maintain critical infrastructure. Sometimes that can lead to very tricky situations. Two of my childhood heroes talked about it openly: Kenneth Reitz is the core maintainer of requests for Python and antirez is the creator of Redis, a key-value store. So one is front-end development and the other one from backend-end. They both talk about burnout here because the burden of becoming an Open Source maintainer on a big scale can very much and very quickly lead to burnout. The internet never sleeps. You never go to sleep. You always get a ticket, a feature request, a pull request, an issue. You always have something to work on, and on top of that, you have to do all your other responsibilities, so that can lead to burnout really quickly. There was one guy who I also respect deeply. His name is Mark Pilgrim. He is the author of Dive Into Python, and he once pulled a 410 for deleting everything [about him] on the internet. There’s actually a term for it: infocide for “information suicide.” He got fed up with the ecosystem, and if you think about the Ruby community, you might remember _why, the author of the Poignant Guide to Ruby. He did kind of the same thing. Focusing on what antirez has said, “once I started to receive money to work at Redis, it was no longer possible for my ethics to have my past pattern, so I started to force myself to work on the normal schedules. This, for me, is a huge struggle for many years. At this point, moreover, I’m sure I’m doing less than I could, because of that, but this is how things work”, so it feels like he feels guilty for maybe being forced into that work schedule and maybe not performing well enough. There are some signs of burnout for me somehow, and it’s that love-hate relationship of Open Source and money. If you accept money, it becomes a job, but you’re not writing code most of the time. You’re writing the talks, reviewing pull requests, you’re looking at issues, you’re answering questions on StackOverflow, you’re discussing on Discord, you’re marketing on YouTube or conferences. When you become popular with Open Source, then it feels like you have a choice between two options: one is depression and the other one is burnout. If your project does not become successful, then suddenly you think you’re a failure, you’re a mistake. It has zero stars; nobody likes it. But if it becomes a success, then everyone likes it, and you get hugged to death. That’s a really unfortunate situation to be in, and you want to stop being overwhelmed with those responsibilities. You have to set clear boundaries and pick your poison. You have to be careful if you accept companies as sponsors. I want to show you one example of how it can work and [point out] some risks. Earlier this year, I started working on a real project that I had been putting off for many years before.

You see, in December 2015, I started a list of static analysis tools on Github. Static analysis tools are just tools that help you improve your code, and it turns out that there’s a lot of those tools. Just starting to collect them was the first step. I didn’t think much about it, but over time that became really popular. And you can see that this graph is more or less a linear increase in stars over time. In 2018, I started really thinking hard about whether there was more than just a Github project here. I talked to many people that I had this idea of building something more from that. It really took someone else to maybe push me over the finishing line and convinced me that this was worth it, and that is Jakub. He said, “why not build a website from it?” and over the course of maybe two weekends or so, we built a website. It’s built with Gatsby, but it really doesn’t matter. We just did it, and then we saw what happened to it. We render 500 tools right now, and the initial feedback was really great. People really seem to like that. We got a cool 720.000 requests on the first day, and over the next week or so, it more or less hit 1.5 million. That was great because suddenly people started getting interested in that project. So we started finding some sponsors. Those companies are special because they believe in your mission, but they also know how Open Source works. They don’t really expect you to advertise their tool. They want to sell to developers, so they want to be in the developers’ minds, saying: “Hey! You are a developer. We built this amazing tool you might want to check it out!” but they also get seen as an Open Source company. I think that’s a win-win. I have to say it doesn’t always go as easily. sometimes companies expect you to just have cheap advertising space. Then they jump off the moment they see you don’t get that many clicks, but others understand that they invest into something that maybe pays off in a year or two from now. So I’m really thankful that some companies understand that mission. However, what companies want is different than what individuals want. Companies want an invoice. Companies want something tax-deductible. Companies want someone that keeps the lights on and is responsive via email, so you really have those obligations, and one platform that helps with that is Open Collective. They have a 501c6 program for Open Source projects that acts as a fiscal host, which means they will do all the invoicing and officially be the maintainers. If you, as an Open Source maintainer or a contributor to a project, want to get [reimbursed for your work], you have to send an invoice to open collective.

I think that’s the best of both worlds. Again, because it’s a very transparent process, companies are in the loop and don’t have to deal with all the financial stuff. But it also means that you have to really polish your public perception. Companies really want to know what they can get out of sponsoring you, and you have to make that very clear. Probably the most important site that you have is not your website, but it’s your sponsors page on Github where you describe the different tiers and what those tiers mean, so we have three tiers: One is targeted at smaller companies and freelancers. They just get exposure, and they get seen as an Open Source friendly tech company. That is a hundred dollars a month. We have a middle-tier, a company sponsor that maybe is a bigger company. They get the batch, too, but they also get a blog post about a static analysis tool that they want to promote, but we make it transparent that this is really a sponsored content. Finally, if you want to go all the way, you go to full content creation, which might be a video workshop, but we don’t have video workshop sponsors yet, so I cannot talk about that yet. I have to say I really would like to try though and it’s cheap really for what you get.

Anyway, those are things that you can do today. Without really changing how you work on Open Source, you can set that up, and you just see how it goes. Maybe no one reacts, and that’s fine. Everything else on that list is kind of advanced. You need an audience, and so you should start with that.

Paid learning material is something that we are doing with analysis tools in the future with a video course. There are companies like tailwind that do that impressively well, so you can learn from them. For merchandising, you have to have a brand. Hence, it’s not something that I could do, but someone like Mozilla or the Coding Train on YouTube could definitely do something like that. Consulting is always an option. Still, it’s also a lot more work and probably takes you away from what you really love, so it really becomes a job. You have to think about whether you want to do that or not. Enterprise services are very advanced [and interesting] for maybe the one percent of projects that can be run in a business and where you have special requirements. I have to say start from the top and work your way down. Start to create an audience. It’s probably easier to build an audience on Twitter and then funnel it back to Github than the other way around. Oh, by the way, did I tell you it’s hard? I really don’t want to end on a low note. I really want to emphasize that I would do it again, all of that if I started today. I think there’s no better time to contribute to Open Source than today. Probably tomorrow will even be a better time because suddenly, way more people are interested, it’s way easier to set up projects, you have all those free tools like VSCode and Github actions, free hosting. It’s just amazing how much you can pull off with very little money involved. So you can try it. What’s the worst thing that can happen? No one cares? Well, okay, then you’re as good as me. But I have some tips for you if you want to start today. My first tip is: “do your homework.” Many people start with learning, and then they build things, and then they close the circle, but there’s one key piece missing here. Some people hate the word, but you learn to love it eventually. It’s called marketing. Marketing means a lot of things to a lot of people, but what it means to me is getting the word out because someone else will if you don’t, and you are awesome; you just have to realize that. Maybe not everyone knows [about your project] right away, so you should really talk about it more. Maybe at conferences, maybe on Twitter, maybe you can just tell your friends. Maybe you can ask people to contribute and to support you. Somehow it’s frowned upon in the community that if you do marketing, you’re not doing it for real, but I think that’s not true. I think that if smart people and patient and passionate people did marketing, then the world would be a better place; because I’m pretty sure the evil guys do marketing. So do your homework, but rest assured that being an Open Source maintainer means running a business, and you are the product. You have to think about why someone would want to sponsor you because if you don’t come up with an answer for that, how should they know. Also, think about the funnel. How will people find you, for example? The best way for people to find you is probably starting a YouTube channel.

There are easier ways, though.

[First,] you can always help out in a different project, and you don’t even have to be a coder. If you are good with design, then I can tell you there are so many Open Source projects that need designers. It’s crazy. Maybe start creating a logo for a small project and start getting some visibility. Another one is having fun. If you know that earning money is hard in Open Source, then that can also be liberating because it means you can experiment and you can be creative, and yeah, having fun is the most important thing, I guess.

Second, build things you love because it’s your free time in the end. The chances that someone will find the project is pretty low, so it better be something that you’re really interested in. If you don’t believe in that, just move on to the next thing. It’s fine if you drop a project that you don’t believe in anymore. No one will hold you accountable for that unless they are jerks, and you don’t want to be surrounded by jerks.

Third, find friendly people because you really grow with your community. You want people that support your project and maybe eventually become maintainers to ease the burden, and that takes a lot of time, sometimes years, until you find one maintainer, so always be friendly, try to put yourself in their perspective. Go the extra mile if you can. For example, reintegrate the master branch into their pull request. Just do it for them. Say thanks twice if you’re unsure.

Fourth is to grow an audience.

Radical marketing is one way, but being approachable and being inclusive is another way. You want to be the guy or the girl that people go to when they have a tough question, or they want to know how to get into Open Source. You want to be the person that helps them out on their first pull request. They will pay it back a thousand times. The most exciting people I have met so far are available for questions, and they don’t really ask for anything in return. You hold them very close and dear to your heart. When the time comes, you will remember those people. We will say, like, “this is an amazing person to work with; I can highly recommend them,” which is called a lead.

Finally, be in it for the long run. Good things take time. You see, it took me 10 years. Maybe it takes you five or maybe even less, but it’s probably not an overnight success. It’s really a long-term investment.